Solving Ireland’s rental market crisis will take time

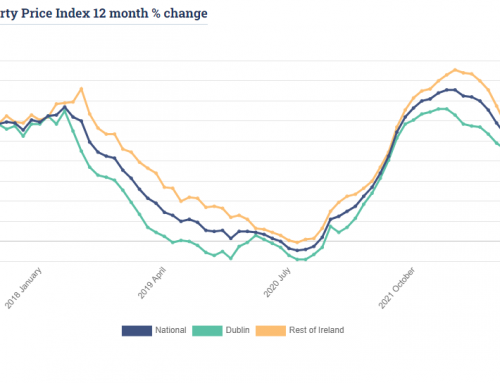

The figures from this Daft.ie Rental Price Report do not make for happy reading for tenants, those worried about homelessness and those whose focus is national competitiveness. Having fallen for almost three years between 2008 and 2011, and then largely treading water until late 2012, rents have now risen for 21 consecutive quarters. The upswing in rents is now not only significantly longer than the preceding downturn but also than the upswing before that downturn, which lasted from mid-2004 until early 2008.

An objective reader will have concerns not just that the trend is persistent but also shows no signs of ameliorating. An optimist might point out that the annual rate of inflation in rents nationally has eased from 13.4% at the start of the year to 11.2% now. An obvious rebuttal is that the rate of inflation remains – for the sixth quarter in a row – stubbornly above 10%. In addition, the quarterly increase in rents between June and September was 3.4%, the fourth largest ever recorded.

The means that four of the five largest recorded quarterly increases in rents having happened since the start of 2016. That’s the picture at a national level, and while the trend is more acute in Dublin, the problem is pervasive. Over the past year and a half, there have been 324 observed changes in rents – one for each of 54 markets for six quarters. Of those 324 changes, just 2 have been falls: a half-percent fall in Leitrim in late 2016 and a similar fall in Donegal in the most recent quarter.

It is tempting to read these figures and demand the government do something. As a society, though, Ireland needs to be far more surgical than that. Otherwise, we run the risk of falling into the classic politician’s trap: “Something needs to be done. This is something. Therefore, I’ll do this.” I would rather those who read these figures demand that the government do the right thing.

And what is the right thing? As I’ve argued in this commentary before, capping rental increases – as the government has tried to do in recent years – tackles the symptoms, not the underlying causes. Some may argue that paracetamol does the same thing and it’s quite effective. But that’s not the appropriate analogy. Caps on rent increases run the risk of ossifying the rental market, in three ways.

Firstly, they discourage churn: particularly with a self-policed system of rent caps, it is far easier to keep a landlord to 4% increases as a sitting tenant than as a new one. This locks out those in the unfortunate position of having to move, for example new arrivers to Irish towns and cities or those trying to start a household. Would you take paracetamol if you knew that, while you’d avoid a headache, three others – largely those on lower incomes – would suffer instead?

Secondly, they may unintentionally prevent new rental supply from emerging. This may be through the loss of incremental improvements to existing supply, as existing landlords decide not to invest in new windows or upgrade the boiler because they won’t be able to recoup that investment in differentially higher rents. Or it may be directly stopping new construction from taking place: with 10% increases on average over the last five years, it is not unreasonable to think that some developers may have planned on 7% increases over the next five years. But their own investors will point to 4% limits, affecting viability of investments, especially in areas outside the “Top Five” rental markets (Dublin 2, 4, 6, the IFSC and South County Dublin).

Lastly, the market may be further ossified by the uncertainty engendered by constant policy changes. A single introduction of caps on rent increases, on its own, would not have this effect.

But there has been an almost constant drip-feed of new announcements and proposals from policymakers in relation to housing over the last few years, none of which adequately address the underlying issue of a lack of supply due to prohibitive costs. Thus, a reasonable investor may look at the market and think: “Last year it was 4% caps on rental inflation; what will it be next year?”. The importance of a stable policy environment – something this country understands when it comes to corporate tax – cannot be overstated when it comes to multi-decade investments like rental supply.

And extra supply is quite simply the only solution. The country needs close to 50,000 homes a year to cater to underlying housing demand – both market and social. More than 15,000 rental homes are needed each year. As I wrote recently in a report for Activate Capital, a state-backed residential finance provider, Dublin alone needs an apartment block of about 200 units to open every week from now until the 2080s

The four other major cities – Cork, Limerick, Galway and Waterford – together need something similar in scale. As it stands, they are starved of rental supply. The graph accompanying this commentary shows the total number of rental homes listed across all four cities on the 1st of November every year since 2006. On that date this year, there were just 251 homes available to rent across all four cities – an almost 90% fall from the number available in 2009.

Those who campaign for improved housing outcomes – from fewer people homeless to better standards in rental accommodation – need to realise that the solution to all these is more supply. More supply improves availability, lowers rents and shifts bargaining power towards the renter.

To build more supply, both profit and non-profit housing organisations need to be able to cover costs. That is where policymakers need to focus. But it will take time.

Irish Rental Price Report Q3 2017 | Daft.ie – Ronan Lyons